An American Werewolf in London - The Surprising Connection Between Werewolf Narratives and Men’s Mental Health Awareness

Such melancholy humour they imagine

Themselves to be transformed into wolves;

Steal forth to church-yards in the dead of night,

And dig dead bodies up: as two nights since

One met the duke ’bout midnight in a lane

Behind Saint Mark’s church, with the leg of a man

Upon his shoulder; and he howl’d fearfully;

Said he was a wolf, only the difference

Was, a wolf’s skin was hairy on the outside,

His on the inside; bade them take their swords,

Rip up his flesh, and try.

The Duchess of Malfi, Act V, Scene II, l. 12-22

Having marked its 40th anniversary last year, much of John Landis’s landmark creature feature, An American Werewolf in London, has been recently (as well as not so recently) celebrated by film-makers and fans alike. There are many ways to describe the movie - as a screwball comedy, a tongue-in-cheek tribute to Hammer Horror and the British Gothic, and as a watershed moment for special effects artistry. Its sense of atmosphere and expert handling of its visceral shocks still hold up decades on, and it is usually the final word in any discussion surrounding the figure of the werewolf in cinema. What more could possibly be said about such a timeless classic?

The opening sequence, a masterclass in mood and tension, centres and references both the disaffected and vulnerable - whether it be the lonely, searching subject of The Marcels song Blue Moon that plays over the titles, the connotations of lost innocence and sanctified suffering that swirl around the name of a strange local pub (‘The Slaughtered Lamb’) or the expertly choreographed bewilderment of two tourists faced with a large and hostile crowd of strangers. What stuck in my mind the most was the circle of silence agreed upon and controlled by the male patrons of that strange little pub. When the landlady suggests warning the boys of the dangers of a werewolf attack, a dart player angrily asks ‘should the world know our business?!’

I was also struck by what is maybe one of the most undersung joys of the film and its screenplay: David Naughton’s subtle, effective performance as David Kessler, a sweet, well-mannered young man, who is forced to grapple with a supernatural and savage curse. Is there perhaps room to interpret the film as relevant not only technically but socially and politically as well, as a horror story that speaks to our contemporary moment? Can we see David as a symbol of the current conversations being had about mental health awareness and the interior lives of young men?

Werewolf mythology, centuries old and defined by its longevity, was once associated quite closely with the emotions. In Renaissance England, though the assorted superstitious frameworks were not as wholeheartedly believed as they may have been in the Middle Ages, cases of suspected lycanthropy were still referred to in either the courts or expository books of the time, as delusional states caused by untreated melancholia (or as we would understand it, depression). As Erica Fudge explains, werewolves were ‘no longer the product of a fleshy, demonic transformation, but of an unstable mind’ (Perceiving Animals: Humans and Beasts in Early Modern English Culture, 2002). In France, 14 year-old Jean Grenier, responsible for the cannibalistic murders of various people throughout 1603, believed himself to be a werewolf, though the magistrate and doctors thought him to be suffering from psychosis.

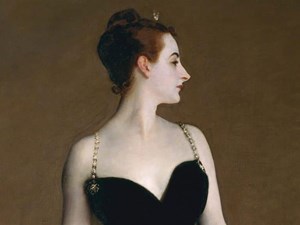

John Webster’s tragic play The Duchess of Malfi, written between 1613 and 1614, features a subplot that addresses these attitudes. Ferdinand, brother of the titular Duchess, orders her assassination but regrets it deeply. As his mourning is mixed with guilt and rage, he slips into an insanity defined by the belief he is a wolf. As a Doctor comments to Marquis Pescara, ‘[he] said he was a wolf, only the difference was, a wolf’s skin was hairy on the outside, his on the inside’. The imagery of hair growing invertedly speaks to an ugliness and deep-rooted shame that has long defined conversations about mental illness, combined with outdated views on masculinity that mean a disproportionate amount of men go untreated and unsupported.

In An American Werewolf in London, several elements reflect and refract this cultural legacy. An early modern reading of David’s lycanthropy as a stand in for mental illness adds further layers of possible meaning. The aforementioned circle or code of silence hinted at in The Slaughtered Lamb imitates the unspeakability that, though work is being done, disrupts attempts to open a more honest societal dialogue regarding mental ill health, especially between men. When David is informed of the death of his friend Jack (Griffin Dunne), his anguished cries and pleas for help are met by an incredulous and slightly fed up Mr. Collins (Frank Oz) muttering ‘this is no reason for hysterics’- as if the inconvenient spectacle of suffering is more of a pressing issue than David’s inner emotional distress. Both Mr. Collins and Dr. Hirsch’s (John Woodvine) interest in David’s health and progress after the initial werewolf attack is limited to the administration of sedatives and detached advice, with Nurse Alex Price (Jenny Agutter) being the only medical professional to engage with David in a truly empathetic and forthright manner; she enters into extended and gentle conversations regarding the content of David’s nightmares and his feelings about the attack and loss of his friend. She is also the only person to approach him without fear when he is in his non-human form. If werewolf transformation has historically been linked to depression, Alex’s final interactions with David can be taken as an important act of reaching out. Even the transformation sequence, with its close-up shots of rapidly growing werewolf hair, repurposes scenes and snippets of dialogue from plays such as The Duchess of Malfi, particularly the Doctor’s description of an inside “hairiness”. The various misunderstandings of David’s plight echo more broadly the difficulties in dealing with and talking about young men’s mental health.

One of the film’s most memorable elements, the conversations shared between David and a spectral, continually decaying Jack, hinge on Jack’s repeated insistence that David committing suicide is the only solution to the werewolf curse. In one scene, as Jack implores David to ‘take [his] life, kill [him]self’, David cries out for Nurse Alex. Taken metaphorically, the repetition of these interactions arguably represent the insidious, isolating experience of having a mental illness, compounded by a heavy blanket of silence, denial, and ignorance that is particularly dangerous for men, who are still seen by some as the unemotional, wholly rational sex. David is unsure how to articulate what is happening to him, and not very many people believe him when he does.

The final act offers further opportunity for thought. Taking refuge in a theatre in Piccadilly Circus that plays pornographic movies, David shares one final encounter with not only Jack but the apparitions of others who have fallen victim to his werewolf rampages. The chorus of blame, defeat, anger, and self-resignation arguably skewers quite gruesomely a societal apathy that, in the worst of circumstances, can lead to increased chance of suicide. The undead victims of David’s ‘carnivorous lunar activities’ recommend numerous methods:

Judith Browns: ‘Sleeping pills?’

Alf: ‘Not sure enough.’

David: ‘‘I could hang myself.’

Jack: ‘No. No, if you did it wrong, it could be painful.’

The ironic comedy of an empty, mouldering cinema with a few lonely patrons implies the equivocation of the taboo of pornography itself with the taboo that lingers over the idea of mental illness. Both are transgressive and uncomfortable, although in wildly different ways. John Landis’s quick, no-nonsense direction of David’s death at the hands of police is quietly sad and makes it easy to wish for a different ending.

Not only are the supernatural thrills of An American Werewolf in London connected by various degrees to early modern understandings of lycanthropy and mental health issues (David’s werewolf status has the potential for double meaning) but the human element that backgrounds the narrative acts as a mirror to the process of “othering” that still takes place towards those who suffer. Landis’s film, then, is not only a fantastic example of genre cinema and wicked black comedies, but a movie that reaches into the past while remaining hugely relevant in our present.